During the 16th century, large numbers of instructional treatises for amateur musicians were published. Thurston Dart and William Coates commented on the heightened interest of amateurs in music instruction during this time period:

By 1575 or so there was every sign of a steadily increasing public and private demand for vocal and instrumental music. London bookshops sold tutors for the lute and cittern, books of printed music paper, and collections of printed and manuscript music mainly imported from the Low Countries; musical instruments were becoming less costly, music teaching less exclusive, musical notation less abstruse.[30]

David Price offered several reasons why amateurs became so interested in music literacy and performance during this era:

By the middle decades of the sixteenth century, and in some places even before then, the reading and writing of music had taken its place within a broadening spectrum of educational possibilities. Literate musical ability was reflected in and stimulated by literature, by travel, by the entertainment or imitation of royalty, and by social ambition. Perhaps this developing literacy was to be seen most clearly in the lives of members of the governing classes but nonetheless simpler expressions of the pleasure of reading and writing music revealed themselves among all classes of society. Indeed the growing number of musical tutors, primers and treatises suggest that a revolution in musical education accompanied that in general standards of literacy, thereby creating its own class of potential musical patrons.[31]

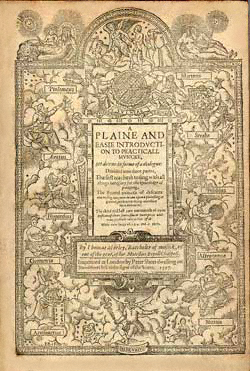

Examples of musical instruction for amateurs included vocal tutors such as Thomas Morley's A Plaine and Easie Introduction (1597), lute tutors geared for amateurs such as Adrien Le Roy's English version of A briefe and easye instruction to learne the tableture (1568), Sylvestri Ganassi's two-volume viol tutor : Regola Rubertina (Venice, 1542, 1543), and tutors designed to assist musicians with multiple instruments such as: Gasparo Zanetti's Il scolaro…per imparar a suonare di violino, et altri stromenti (1645, for violin, viola and cello).

Although music tutors for amateurs first became popular during the Renaissance period (1450-1600), during the Baroque period (1600-1750), the popularity of music tutors increased dramatically. Boyden commented on the popularity of tutors for musical amateurs, in particular, ‘do-it-yourself’ violin tutors:

The first violin tutors were essentially 'do-it-yourself' books. Often regarded as a modern phenomenon, such books flourished during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries not only in music but in many other fields as well, and they furnish a vivid social commentary on the times.... Perhaps more important, the appearance and continuing publication of these elementary manuals show that the violin had ceased to be the sole property and concern of professional violinists and that it had begun to appeal to a far broader social group among players.[32]

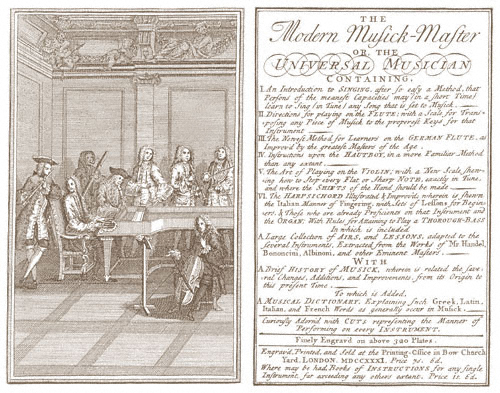

Between 1658 and 1731, over thirty amateur violin instruction books were published. [33] A sampling of these early publications include John Lenton's The Gentleman's Diversion (1693); John Playford's A Brief Introduction to the Skill of Musick (the 1658 second edition contained a section entitled “Playing on the Treble Violin”); Nolens Volens or You shall learn to Play on the Violin whether you will or no (1695, author anonymous); The Self-Instructor on the Violin (1695, author anonymous); Peter Prelleur’s The Modern Musick-Master (1731); Robert Crome’s The Fiddle New Model’d (1741) for violin, and his cello tutor The Compleat Tutor for the Violoncello (c.1763-1776). Notable features of tutors written by Baroque composers such as Crome and Prelleur, were illustrations of the violin fingerboard to assist beginning violinists in knowing where to place their fingers (Crome also included a cello fingerboard illustration in his violoncello tutor). Music historian Robin Stowell asserted that these early violin tutors enhanced the status of playing the violin: “These publications served a valuable purpose in helping the violin rapidly to gain social respectability in competition with the viol.” [34]

© Copyright 2025 RK Deverich. All rights reserved.

Although this online violin class is provided free of charge, all rights are reserved and this content is protected by international copyright law. It is illegal to copy, post or publish this content in any form, and displaying any of this material on other websites, blogs or feeds is prohibited. Permission is given for individual users to print pages and perform music from this website for their personal, noncommercial use.